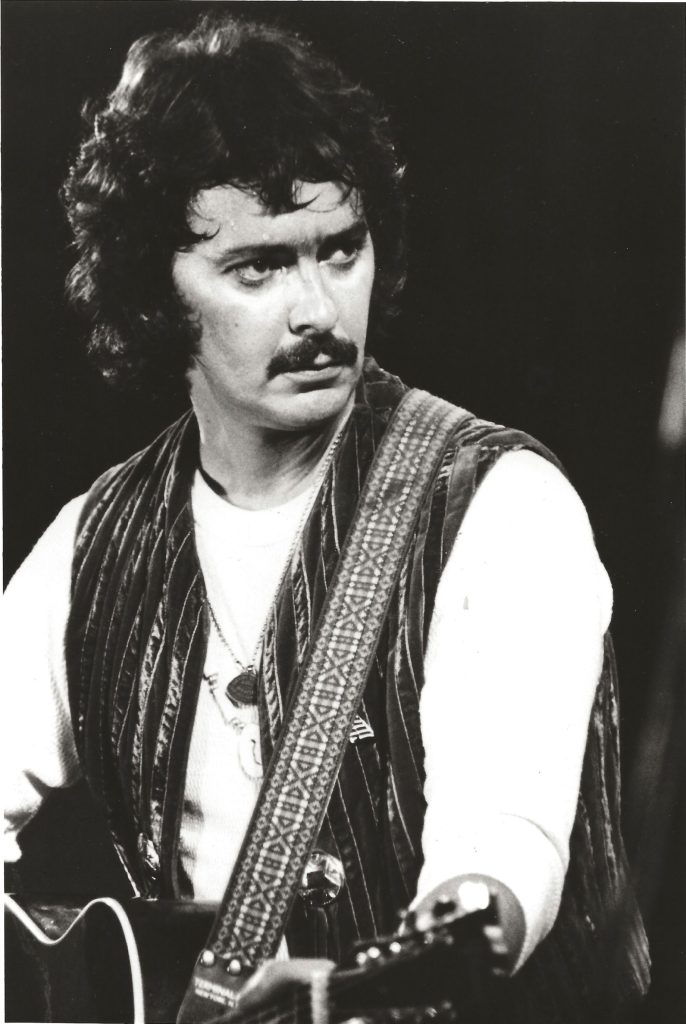

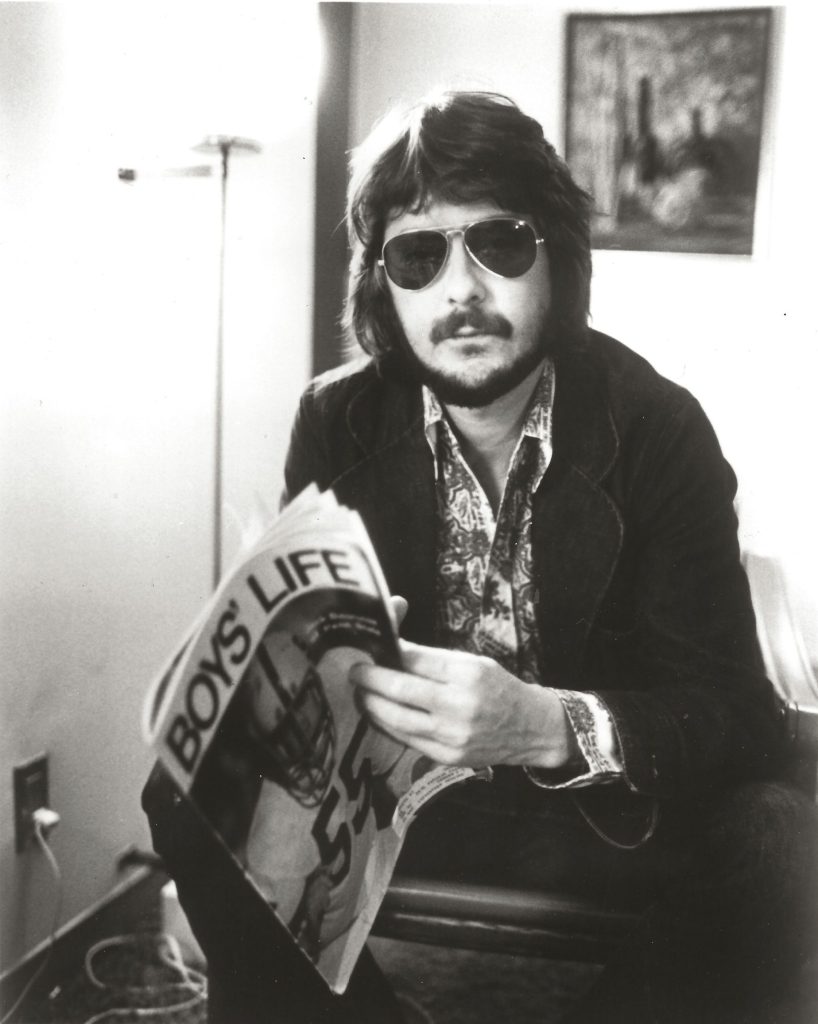

I first knew Bob Neuwirth as a legendary hipster put-down artist: the person who, with Bob Dylan in the early 1960s, would sit in a Greenwich Village bar, waiting for people to approach and attempt to ingratiate themselves, and then destroy them with deadly cutting remarks.

5 December 2023

To NEH Media Projects

From Greil Marcus

Re: documentary film “Bob Neuwirth: The Anonymous Hipster”

Or as the the person whose words close Eric Von Schmidt and Jim Rooney’s 1979 “Baby Let Me Follow You Down: The Illustrated History of the Cambridge Folk Years” described himself: “There are some who’ve got the patina, but there’s a gap between the soul and the patina. The true enjoyment of being an existentialist is not available to them.” For a virtual transcription of what this miasmic aggression sounded like, one only has to listen to Bob Dylan’s 1965 “Ballad of a Thin Man.”

I first met him in 2005, when the late record and concert producer Hal Willner was staging a multi-artist event in New York to celebrate the publication of “The Rose & the Briar: Death, Love and Liberty in the American Ballad” (Norton), which I had edited with Sean Wilentz. Bob was there to perform the strange song “I Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground,” first recorded by Bascom Lamar Lunsford of North Carolina in 1924 (and one of three songs taken up in my “Three Songs, Three Singers, Three Nations” (Harvard, 2015).

He was warm, funny, friendly, modest, and full of enthusiasm—the complete opposite of his reputation. He was eager to talk about painting, music, his admiration for the other performers present. His performance that night, by means of changing a single word in the classic version of the song he sang, was a revelation.

A few years later, when I was teaching a course in old American folk music as form of common speech and common history at the New School, I was walking down a Greenwich Village street at night when my wife and I passed a couple coming toward us; the man had a hat pulled down and was talking quietly to the woman with him.

I never saw his face. We were a block past when I realized we had passed Bob Neuwirth: his voice, quiet and scratchy, a film noir voice, was that distinctive. I hadn’t caught a word, just the tone, which contained thought, inquisitiveness, wariness, and suspicion. We had exchanged numbers in 2005: I called him that night and asked him to come to my class, where “I Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground” was a central focus, and perform the song the next day. He did, and the class was transfixed—and, as it happened, did the same for the next six years, each time prefacing his performance with a different talk about aspects of the 1960s folk revival—“the folk scare,” he called it—which was unfailingly hilarious, personal, historical, and instructive by turn, if not all at once.

Bob Neuwirth was a savant in the shadows of the story of his time as it is usually told—a sort of incarnation of “The Prophet” in “Moby-Dick,” speaking from the alley. With vast knowledge of folk music, modern art, the bohemian culture of New York, Los Angeles, and many other places, he was a bad conscience of the era he almost invisibly defined (if one looks at the 1967 Donn Pennebaker film “Don’t Look Back,” about Bob Dylan’s 1965 tour of the UK, he’s always at the edges of the frame, his face all but hiding itself, but if one looks closely, he is a fulcrum turning the ideas and actions of those around him), doubting the great promises others made, but never turning his back on those around him, or those who were drawn to him, facing what were not merely personal but shared demons, using the fact of his own struggle against alcoholism to help others, especially musicians and artists, over to the other side. A sense of jeopardy, compassion, and flinty skepticism was his gift to others and his time.

There was no one like him, and that is why a film about him and the years he shared with so many others is such an intriguing project. I deeply believe it deserves whatever support it may receive, and I look forward to being part of it.

Other than those mentioned above, my books include “Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ’n’ Roll Music” (Dutton, 1975), “Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the 20th Century” (Harvard, 1989), “The Shape of Things to Come” (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2006), “Under the Red, White and Blue: Patriotism, Disenchantment, and the Stubborn Myth of ‘The Great Gatsby’ (Yale, 2020), and “Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs” (Yale, 2022).

With Werner Sollors I am the editor of “A New Literary History of America” (Harvard, 2009). Since 2000 I have taught at the University of California at Berkeley, Princeton, the New School University, the University of Minnesota, NYU, and the CUNY Graduate Center.

Greil Marcus